Writing about Work

in poems and prose

One of the first poems I wrote as an adult was about work. “Dad Goes to Work” takes place during the Vietnam War when my dad was in the Navy and as he goes to sea. It looks at my life as a child on Oahu in the six months between his leaving and returning.

Recently Erin Murphy put out a call for unpublished poems for an anthology, The Book of Jobs: Poems About Work. Published on Labor Day, The Book of Jobs includes “Dad Goes to Work” among 134 other poems on a thrilling variety of jobs, all available to read for free at One Art and with an Open Access Edition forthcoming from Penn State University Libraries in 2026.

I have had many jobs, and the anthology reminded me of how often I have written about work. Another early poem, “Looking Right,” in my 2nd poetry collection, Luckily (Anhinga Press), takes place at an interview for a job I don’t want:

LOOKING RIGHT

When I interviewed for the grant research job at the hospital,

I was nervous and tried to remember what my boyfriend said,

that I’m a plum, a natural.

I thought the interviewer would talk about grants or research

or fundraising in general, but her first subject is makeup.

I am allowed to wear foundation and powder, but it must be

natural and correspond to my skin coloring. Mascara is okay

if applied lightly; true lip tones are acceptable. Nail polish

may not be worn longer than four days without a fresh application.

My hair must be in an easy-to-maintain style and may be

confined by a gold, silver, or tortoise shell barrette without

ornamentation. One small inconspicuous post earring per ear

is allowed (pearl, diamond, gold, or silver only) as long as they

match, do not exceed ¼”, and are worn in the lower lobe.

I learned the hospital has its own gas station that accepts payment

in payroll deduction. On my birthday, I can receive 25% off

in the gift shop; however, I am only the first applicant, there are many

after me I’m told, and they may re-run the advertisement.

It will be a month before the job really starts, but if I am

the lucky applicant, in five years I will be fully vested.

I don’t know what vested means, but in eight weeks I hope

to have made enough money to move to New York and never

see this hospital again. I don’t even like General Hospital. On TV,

Heather Locklear was late for her interview, arrived in a tank top

(scoop neck, a hospital no-no), and was hired on-the-spot.

For this $13 an hour job I may wear only solid-colored suits

(no pastels), navy blue, hunter green, many shades of brown,

and oddly, purple is okay. My jacket may have non-patterned buttons

in a color that matches the fabric. The interviewer’s blinkless eye

contact reminded me of an owl I saw in the park, staring at me

as if through two holes in a wooden fence. Hosiery is required.

Skirts must be straight, A-line, or pleated with hemlines no higher

than just above my knee and no longer than the bottom of my calf;

they must be easy-care synthetic or a natural fiber that looks like

linen or fine wool. The skirt may be fleck-patterned if, from ten feet

away, it gives the appearance of an approved solid color.

Bold plaids, lavender, pink, yellow, and mint green are banned.

A few departments allow female employees to wear pants,

but no knit fabric slacks. It was nearly 100 degrees outside,

my hair was wet and curling with humidity, forehead shining,

as I learned that turtlenecks are allowed, though no cap sleeves,

no sleeveless, no orange, rust, deep green or bright yellow.

I may not wear a shoe with a clear plastic heel or toe straps.

I am not allowed to have bad breath or other offensive

body odors. If I do not have my childhood immunization record,

I will receive shots for measles, rubella, tetanus, hepatitis B

and chicken pox. They will x-ray my chest. When I left,

the interviewer did not meet my eyes. In the rain, I lost

the parking garage, and by the time I found it, I had blisters

on both heels. I drove away so fast, I had to drive with just my feet,

my arms stuck in the navy blue suit jacket I was twisting off.

I wrote about having no sense of direction and taking a job in the Mapping Department in “The Cartographer’s Assistant” published in How to Live: A Memoir in Essays (Tupelo Press 2023), originally published online at New Orleans Review: The Cartographer’s Assistant.

In the essay, I focused on my mapmaker’s assistant job as well as on the political environment regarding welfare reform that really accounted for my job being created: The Personal Responsibility and Work Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) which replaced Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC). States were encouraged to be creative in their welfare-to-work efforts. Part of this effort in Orlando was the creation of my job. It consisted of taking calls from people without cars who were being pushed off welfare if they didn’t work. Pre-Google Maps, it was my job to find them on a map and to determine the best transportation for them, and to arrange it. No one knew I couldn’t read a map.

I first wrote about working for the mapmaker in the context of working several temp jobs in the poem, “The Cartographer’s Assistant,” also published in Luckily:

THE CARTOGRAPHER’S ASSISTANT

Temping for the bus company was like eating lunch

at Chik-Fil-A under lights so bright in a booth so small,

you’re practically falling into each other’s pores,

having to eat with your eyes closed. I had no sense

of direction because of seventh grade geography,

my unsmiling, full-lipped teacher had assigned me a partner

before we went outside to measure the sky,

but I’d been deserted, left staring at concrete, a sharp edge—

Frank Eidson, a boy in a blond corduroy jacket that matched

his hair, took pity on my pink & yellow sunflower pants

(my mom’s—we could wear jeans to school on Fridays,

but I didn’t own any because Mom said the dye would wreck

her dryer), & Frank pointed, said a few words—compass

points of kindness, nothing concrete—geography went downhill

after that—map phobic, lost on every road. In my eighth floor

cubicle at the bus company were yellow wall-sized & computer

maps—my job: find transportation for people being kicked

off welfare, get them to work or school. Each person given 800

transportation dollars. I suggested we buy them cars,

but the blond mapping woman said that’s interesting in a coffee

philosophy way, & no one got a car, people calling me

to get to work at Trader Vics or McDonalds—no buses available,

no carpool—they all took cabs, almost $40 a day. I don’t think

anyone made that much in a day, wondered how they’d get to work

when the money was gone. I learned to find each person

on the map—like looking for something you’d lost, scouring

square inches—I called cab companies to pick them up,

take them home. There was a glass window around the entire floor,

& some days I’d think of pitching myself through it to relieve

the air-conditioned boredom. When they offered me full-time,

I thought, just spin me around twice & ask me to point north,

I’ll be free. It was worse at Pilgrim Insurance, looking up

4,000 zip codes a day —no windows, no private cubicles, just

a tiny chair with a seat nearly the size of my butt. Then,I temped

in a trailer for the developer who tore down the old Navy base

where I grew up, I could look out the portable window & see

the excavated dirt that was the hospital where my son was born—

the Office Manager had saved bricks from the base but wouldn’t

give me one. I tried this job twice, but couldn’t remember

which way to feed letterhead into the printer, the boss watching me—

& I cried as secretly as possible, turning toward the corner,

but later they brought in another temp who baked them brownies,

& they moved me behind a felt gray cubicle wall,

with a laptop, and no work—just sitting, looking at the carpet wall.

Before, I’d had a phone & a window, & Michael had called once,

said, You sound like you’re convalescing. When I was tired,

direction was the first to go.

I’d written poems from working for an opera company:

LITTLE WING

Charles decorated Nagasaki with cut petals, thousands

of pink and white stars to throw into Cio-Cio San's hair

like a night sky. On the fire ladder, I swayed

as if over sea, reached the fly loft. On a gangplank of sails,

I looked up into a giant harp, as if I were nothing

but the music inside, scenery below flying on ropes — cream

Austrian drape, American flag with 45 stars. It's the early

twentieth century, a 999-year marriage contract with a monthly

renewal, teenage girl like a delirious bird, here come the flowers,

here comes the moon, little wing. My red-haired neighbor

was Suzuki, wringing her hands outside transparent paper walls

when the sailor stayed away, no parasols, no fans.

The bird girl killed herself with her father's knife, sailor off

in the distance calling. He may love her sideways, but the facts

are bald, her heart fasting. When I called you, and a woman laughed

like a banjo, refused to let me speak to you, I rocked without

a rocking chair. Night after night, the same story told, drapes fly,

a giggling cloud of flowers, the girl's devotion escaping back.

(Five Kingdoms, Anhinga Press)

PINKERTON & BUTTERFLY GO TO THE DOLLAR MOVIE

In the morning, when I went to work, Pinkerton & Butterfly

were sitting on the front steps of the opera house, knee to knee,

doing a crossword puzzle. They looked up smiling, asked directions

to the dollar movie.

Because love can be like that, one minute you’re at sea

& the next you’re shoulder to shoulder reading newsprint

close as a slit throat, an obi—little package carried on your back,

little gift.

MARGUERITE

My aunt Marguerite bathed three times a day

because her nerves were burning shingles.

As a girl, she had beautiful waist-length hair.

Everyone loved her sister.

When her sister died, she knocked on her stone,

twice, as if it were a door.

~~~~

At the opera, an elderly man mistook me

for Faust’s Marguerite,

blond, with small lines

like papercuts under her eyes. In prison

for murdering her child, she made a baby

of straw, rocked him. Mephistopheles flew in

from Houston with his three-year-old son,

who played the part of the baby.

Dressed in a white sheet, he comes from heaven

in the final trio. On the second night,

he got distracted waiting for his cue

by the curtain, came toward me,

a little sail, until the stage manager pulled him back.

When my son died

a thousand miles away,

I made my arms a cradle.

~~~

The veil over our eyes is thin,

the dead visible like candles through gauze.

Our souls relax at night,

and they are everywhere in the dark—

on the paths in the fields, in the wind,

alongside the living

with small lamps, sometimes flowers,

a heart or wreath made of pine.

(Underwater City, University Press of Florida)

PINKERTON

writes a love letter on blue paper

cries his blackberry voice

(you could lick his tears)

time brambling

cleft

oh lead us into a high mountain

into ourselves—

snow, so as no

fuller on earth can white

(Luckily, Anhinga Press)

ANNUNCIATION

It was like meeting Madama Butterfly

backstage,

but without that nervousness &

animation,

like standing in the lattice

watching the day-old birds lift up their

heads, dark eyes, open their mouths wide,

then settle down against each other

for sleep,

the door

that had been closed to him,

& then the trees

in the yellow moon he made around,

reading my mouth, & all our clothing

had about it the flowers they occasionally crush,

leafy trails which when embroidered, transform

the embroidery on the birds’

wings in the nest,

orange falling across

like Gabriel’s when he leaned in to comfort you.

I’d written about working in a homeless shelter:

IMMORTELLE

The men sleep on deep blue mats, head to foot, in a metal tent,

windows open to keep them from panicking.

Weapons aren’t allowed, but maintenance found dozens

of knives under the shed, clattering like silverware.

The children think the leaves of my green plant are flowers, a boy

carries a leaf high in the concrete yard, waving, girls taking

turns carrying the plastic pot, one girl asks if she is doing a good

job, balancing saucers and bells, trumpets, sweet everlasting.

33 REASONS NOT TO ATTEND THE WHITE HOUSE CONFERENCE

You will be required to show up in Tampa at seven a.m. to register.

You will drive to a hotel in Tampa the night before & get lost on

the one-way streets. You will request a non-smoking room & be

given a room full of smoke. You will become claustrophobic

in the elevator because you don’t know how to insert your room

card to open the elevator door. You will pay sixteen dollars for

a fish sandwich because you are too tired to find a restaurant.

Your boots are not made for walking the four blocks to the conference,

though they are sleek. You are not wearing a blue suit. The White

House speakers appear to be three cheerleaders in their early 20s

with bouncy hair, abundant make-up, and end-of-sentence lilts.

Jeb Bush will speak & receive a standing ovation. You & two

Catholic ladies will remain seated. (It is not that you are prejudiced

against men named “Jeb”—you liked the one on Beverly Hillbillies.

But that was Jed.) Attorney General Ashcroft will speak & receive

a standing ovation. You & two Catholic ladies will remain seated.

Ashcroft will imbed seven manipulative stories into his speech,

one involving a boy with Down’s Syndrome who sang with him

at church. The federal security guys are spaced a foot apart all

around the room. You will wonder if the feds notice you don’t clap

or give a standing ovation & wonder if this is considered a minor crime.

One of the feds will seem to find you attractive, smiling while you eat

your vegetarian wrap with no dressing, inching closer, as if all the

security guys are playing a game & taking the place of the man in front

of him at designated times. You wonder if the security man will decide

you are a Communist & put you on a list, or at least put you on a list

of non-Republicans. You will want to stand up when Ashcroft

is speaking & ask a brief question about the war. You wonder how

the security guys would respond to you behaving like a citizen

of the United States. Jeb & Ashcroft both have remarkably pink

skin, the way a baby brought back to life is said to be pinking.

Either Jeb or Ashcroft will say that he is building the first faith-

based prison. You & the Catholic ladies will look alarmed. Jeb

or Ashcroft will receive a standing ovation. One of the Catholic

ladies will tell you that in Pennsylvania there were homeless people

who lived well, & you will want to show her the shelter in Orlando

with 750 people living in an old TV station from the 1950s,

including Mary and 185 other children under seven years old.

When the blond-bobbed cheerleader comes back out, one of the

Catholic ladies will say, Here’s my favorite. You will fall asleep

in your chair even though you’ve had six cups of coffee. The coffee

stand will close, its register tape finishing a celebratory wave, though

you still have to drive home. When you decide to visit a Cuban-

American poet instead, you pass a restaurant called the Seven Seas,

the side wall a mural of a woman’s head with the body of a crustacean.

Though you need to eat dinner to balance the yin of six cups of coffee,

you are nauseated by the Shrimp Woman. You pass Armenia again—

at Thanksgiving it was the mark of too far. You pass S. Rome, making

you sad for the winter gone in central New York, missing M. and the

snow angel. When the Cuban-American poet is running late, you will

consider putting your head down on your table in the bookstore,

like in elementary school when you’d had enough.

(Five Kingdoms, Anhinga Press)

I’d written poems about working in a health food store in my first book, Underwater City:

COLONIAL MALL I

An old woman

came in

slow

and asked

where the old

girls were—

I told

her none

were working

that day,

and she said,

“Tell them

my husband,

the one

with two

canes, died.”

(Underwater City, University Press of Florida)

COLONIAL MALL II

A girl was wheeled fast through the mall,

she was lying flat on a high bed,

and her face was sideways

toward the window of my store.

A small and roundish woman pushed.

The girl’s face was wild,

mouth stuck with fear,

her eyes pulling

everything she saw inside.

Her hair didn’t fit on the bed,

it fell off the end,

so long I wondered how

it didn’t catch in the wheels,

her hair flying as the bed

drove by.

The round woman didn’t seem

big enough to be pushing that fast,

the bed seemed to go on itself

then, the wild Rapunzel girl

saw me

and she pulled me inside.

BIRD IN SPACE

after Brancusi

All the other cashiers ran into the stockroom when the testy woman with the gauze

covered face came in, the square of gauze growing bigger each week until it couldn’t

cover the black in her cheek, moving toward her nose like ants on the march, black tattoo.

She became nicer then, smiled, said thank you, and one day told me about a cave

in a hot dry country that she’d entered with her sister, exposing themselves to an agent

that had first killed her sister and was now chink chinking away at her.

I imagined something like the thick yellow powder scattered around Egyptian tombs,

but didn’t ask, just rang her groceries, wanting to unhitch her copper bracelet, tiny

thorns jabbing every which way, little crown around her wrist, face silting up, like a

lake filling with sediment, turning to marsh, anatomy eliminated, revealing she’d gone.

I wrote about teaching English as a Second Language:

Second Language

My first summer as a teacher

in an international language school,

the Croatian students dressed me in white,

a wedding dress, Iva and Jane insisting

I play the runway game in the portable

classroom. The purpose was vocabulary

building—one student acts as model,

walking the stage, while another

is the announcer, describing the outfit

for the crowd, but they howled

so loudly at my modeling, I couldn’t

hear the details of my dress, plucked

a cathedral train, the soft hand

of chiffon, though by then I wasn’t sure

they were even speaking English,

doubled over, hysterical, hair sweeping

the floor, the students next door giving

up on their lesson, joining us with their

teacher who I had loved once, and wished

that I could marry, the girls like fairy

godmothers intuit this,

gowning me.

Their own city singed from war,

fields and villages mined.

At the mosaic table in a coffee house,

I learned to say I love you in Croatian,

Volim te, we said it in every language

we remembered, laughing because it’s

always the third phrase you want to know:

hello, goodbye, I love you.

Their imaginary dress fell over my hair,

like a wish sweeping winter from another

country, as if they could bequeath me

love, like that white dot, the moon—

suicides abandoned in the trees,

the sullen blowing bubbles in the mud.

I wrote about working for an artists-in-residence program:

1984

Allen Ginsberg wrote on the wall

of my closet twenty-two years ago,

on the half-moon after his birthday,

& said he’d left flowered Japanese

napkin holders here—a gift for us,

his handwriting happy & big as mine

when I was a girl, the letters brushing

my clothes, as if I could walk back

a bit, sit with Allen, but when I sleep

in his bed, I don’t dream of him

or anyone else who slept here: not the side-

by-side of William Stafford & his wife,

not Carolyn Kizer’s crowny hair

on the pillow, not Ferlinghetti crayoning

his name across the wall; instead,

I dream of telling Ann why I think she’ll find

a man even though almost everybody in this town

is old & retired, the men walking down the beach

in wide-open shirts, blown about. Another night,

I go so far away, I wake up on the bridge

to the sea where there are glass sandals, flowered

& skewed no walking way

as if whoever left them lifted out.

But now the people are arriving with plastic

bags & their investigation of the sand,

and the ocean is telling its story

from the beginning. Allen, I think someone

took the napkin rings, I mean, we don’t even

have napkins, but thank you for thinking

of us & leaving these invisible things.

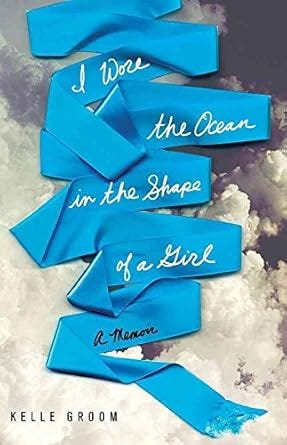

I’d written about my first job at 17 as temporary secretary for the Weapons Department of the U.S. Navy in Rota, Spain in a chapter of my memoir I Wore the Ocean in the Shape of a Girl (Simon & Schuster). Another chapter in I Wore the Ocean in the Shape of a Girl, “Shelter,” takes place in the homeless shelter where I worked for three years.

There are many more instances, but one thing I’ve noticed is that I almost always begin with a poem. The poem usually keeps the focus tight – a moment or series of moments. In an essay or memoir chapter, I can open that moment up and make something expanded and new.

If you’re interested in writing about work, you could think of a moment that has stayed with you. As you can see from these work poems, it can be anything – a complaint, a frustration, something you’ve seen that you can’t understand, something that was revealed like a curtain opening for a second…

See what happens. If you like, let me know how it goes. I would love to hear.

Perfect way to start my day. Thanks, Kelle.